The car crash that killed his father changed Richard Onyait’s life in profound ways. Born in the town of Soroti, in eastern Uganda, Richard was just 10 years old at the time of the accident, and he visited his injured father at the hospital after school each day. There he witnessed doctors and nurses showing compassion and love for his dad, who eventually succumbed to his injuries.

“After that experience, I felt the desire to go into healthcare, with the hope that I would help another little boy not lose his dad,” says Richard.

His father’s death also radically altered his family’s circumstances. As an engineer working for one of the nation’s largest firms, Richard’s father had been the sole breadwinner. With his passing, Richard’s mother, a homemaker, had to find work to pay for her son’s schooling. This meant the 10-year-old boy had to shoulder most of the housework in addition to his studies. Without the firm discipline of his dad, who was a star student in his own youth and the pride of his extended family, Richard also had to learn to motivate himself.

“I grew up really fast,” he says. “When my dad passed on, I think my mind kind of switched from being a child to an adult. I realized then I only had Mom, and we had to make everything work.”

Today Richard, 40, lives the promise he made to himself while watching people care for his dying father. He is a registered nurse leading a team in a Madison, Wisconsin, emergency room.

“Nursing is a calling — you are called to serve other people at a time when life is challenged by illness, disease, disability, old age,” says Richard. “I wouldn’t do anything else better than nursing.”

Richard’s success has come at a great price, however. He is separated from his family, including two daughters he hasn’t seen in eight years, and effectively had to restart his medical career after immigrating to the U.S.

Building a Career in Uganda

Richard originally studied at Makerere University, Uganda’s oldest and largest university, in the capital, Kampala, and became an orthopedic clinician, roughly equivalent to a physician’s assistant in the U.S. medical system. Drawn to orthopedics by a desire to treat the same kind of multiple bone fractures that took his father’s life, he also formed a student fraternity that focused on providing free healthcare to rural members of his own Teso tribe, who suffer from lack of access to modern medical care and facilities.

Through that relief work and the connections he made, Richard gained a scarce hospital job. He soon found himself healing broken bones in the ER, empowered to do everything for patients except perform surgery, he says. Days were long, often 13 hours, with weekend shifts as well, but the work was rewarding. He was promoted and began teaching students.

Then Richard’s trajectory shifted again. Richard made the difficult decision to start a new chapter almost 7,000 miles away from his homeland.

A New Life

Richard emigrated to the U.S., landing in Boston on a frigid winter day in 2015, and eventually connected with a refugee center run by Boston Medical Center.

“The Boston Center for refugee health played a remarkable role in helping me regain my sanity,” he says. He lived with a friend until, after a year and a half, he received approval to work. He took a job at a nursing home, where he met a patient suffering from a spinal cord injury that left him paralyzed from the neck down and unable to use his hands or legs. The patient asked him for a big favor: to stay with him in his home in Wisconsin and tend to him until he found a local caregiver, then return to Boston. Months later, they were still together, Richard simultaneously helping his patient get ready for the day and earning a bachelor’s degree in nursing at Herzing University, in Madison. From there Richard entered a rigorous University of Wisconsin nursing residency program and finally received permanent residency status.

Today he marvels at his journey back to the ER and how his daily practice is both the same and different from his days in Uganda. “The basic knowledge application is the same, but the equipment, the resources, and the workflow is very different,” he says.

When he worked in Kampala, paper charting was still standard, but in Madison patient data is recorded electronically. Instead of malaria, he more often sees heart attacks and strokes. He also misses his family, including his daughters, and hopes to gain citizenship in order to bring them to the U.S., a country he credits with giving him another chance at his dream of caring for people.

“I’m always grateful to America for giving me a second opportunity to live,” says Richard. “Because my life was at a crossroad, and I probably would not be here today if it hadn’t been that a few things went right for me.”

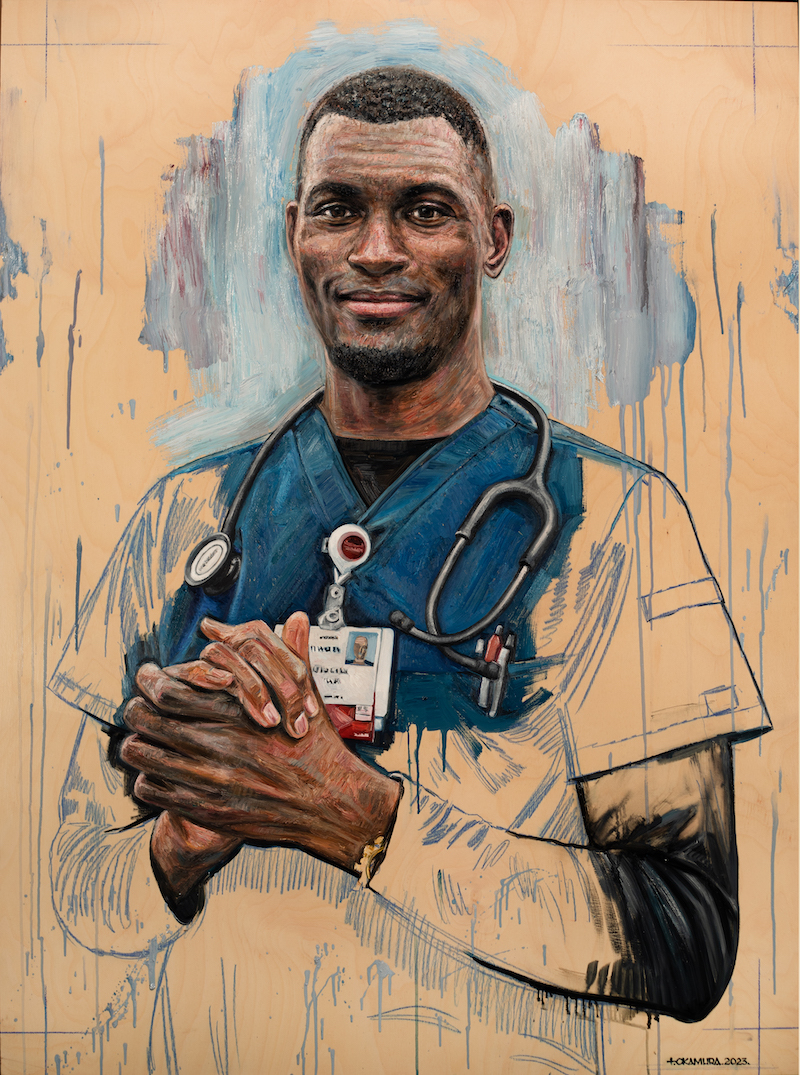

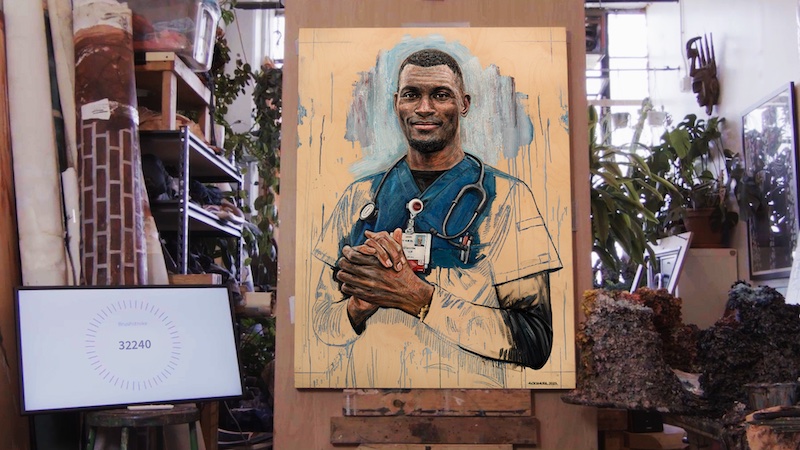

Richard was one of the subjects of GE HealthCare’s Canvases of Care campaign for Nurses Week. New York–based artist Tim Okamura has created paintings of Richard and four other nurses. Each painting contains one brushstroke for every hour of care the nurses have put in over the course of their careers — Richard’s has 32,420 strokes — and the paintings will remain unfinished, because a nurse’s work is never done.